In 1941, Arkansas operated eight state parks. Seven were open only to white visitors. The eighth was set aside for the second-class citizens politely called Negroes.

Peaches were a major cash crop in Arkansas back then. At now vanished Highland Peach Orchard, south of Murfreesboro, nearly a million Elberta peach trees reached as far as the eye could see.

Fox hunting still took place in rural Arkansas eight decades ago, but without the English tradition of riding to hounds. Local hunters preferred to relax outdoors with a smoke and a drink while listening for the distinctive bark of each dog pursuing the fox.

Toby shows toured the state’s rural areas before World War II. The barker, known as “Toby,” would hawk candy boxes touted to contain tickets for winning a plaster elephant or some other gewgaw. Then he and a couple of supporting players would pass the hat as they entertained the crowd with homespun comedy.

And in Little Rock as the Great Depression ended, a dozen homeless families lived in shacks of scrap lumber and tar paper on a riverfront patch known as Squatters’ Island. Viewed as a tourist attraction, they grew tomatoes, okra, peppers and pumpkins in the alluvial soil.

Those time-warp nuggets and countless more are scattered among the lodes of information, much of it fascinating and some even amazing, in the 448 pages of “The WPA Guide to Arkansas.”

The book, created for the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration by a platoon of federally paid writers and editors, was printed in 1941. It was among the last of 48 state guides published, starting in 1937, by the agency’s much debated Federal Writers’ Project. The series also included the Alaska Territory, Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.

Reprinted in 1987 with a fresh introduction as “The WPA Guide to 1930s Arkansas,” the original volume wafts today’s readers back to what was then the mainly rural “Wonder State” but soon to get a new nickname: “Land of Opportunity.”

Today, Bentonville has 54,164 residents and the 2020 Census estimated 546,725 residents in the Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers metro area. Bentonville’s population in the 1940 U.S. Census was 2,359. Springdale’s was 3,319. Rogers’ was 3,550. Fayetteville’s was 8,212. The combined count of 17,430 in 1940 was handily surpassed by the 21,290 for Pine Bluff — then the state’s fourth largest city, now down to No. 10.

The guide’s 1987 edition can be bought online for $25 to $40 or read for free at some libraries (there are other reprints as well, including one by Trinity University Press in 2013). The 1941 original sells in some venues for hundreds of dollars. The contents portray Arkansas at a fracture point between the Great Depression and U.S. entry into World War II. Countless sights, often routine back then but vanished or altered now, flash by on the guide’s eight city tours and 17 driving routes (sometimes on unpaved state highways).

POTPOURRI OF TOPICS

Preceding the extensive touring sections are 19 essays on a potpourri of topics that shed light on public and private life eight decades back. Among the subjects are Natural Settings, Archaeology and Indians, History, Transportation, Agriculture, Recreation, Religion, Folklore and Folkways, Government, and Music.

In charge of the guide when the project began in 1938 were notable Arkansas literary figures Bernie Babcock and Charles J. Finger. They were soon replaced by Dallas McKown, who completed the process under the sponsorship of then-Secretary of State C.G. “Crip” Hall. The list of consultants mentioned 147 contributors.

“To obtain information for the guide, workers of the Arkansas Writers’ Project have haunted libraries, handled countless faded documents in archives, and have read hundreds of books, magazines and newspapers,” McKown wrote. “They have driven thousands of miles over highways that crisscross the Delta, slice through deep pine forests, follow river valleys, and ride the ridges of the Ozarks and Ouachitas.”

The Federal Writers’ Project drew persistent criticism nationally from conservative quarters, notably the House Un-American Activities Committee. Charges by the committee focused on alleged Communist connections or sentiments that were never substantiated. The accusations included the supposed promoting of racial integration, at a time when Jim Crow laws ruled the South and racial discrimination was widespread elsewhere.

“The WPA Guide to Arkansas” contains no evident sympathy for any easing of legal segregation — much less ending Jim Crow laws. Separate public facilities are mentioned as a matter of natural course, as with “Watkins State Park (for Negroes), 8.9 m. NW of Pine Bluff on U.S. 270.” The park is no longer on the map.

STEREOTYPES in 1941

Black communities are covered on the eight city tours and elsewhere in the guide. But urban Black people are often depicted in stereotypical terms as happy-go-lucky sorts looking mainly for a good time. Comments about rural Black people can be even more offensive, focusing on ignorance and superstitions. Reading them in 2021 would offend many readers of any skin color.

The guide also echoes some stereotypes about backwoods white Arkansans, as in these descriptions from a route through Newton County south of Jasper:

“The women wear sunbonnets, and many of them use snuff, taking a small quantity on the end of a ‘rough elm toothbrush,’ and chewing it like plug tobacco. Hill people consider dipping snuff, or putting it on the lower lip, an unclean habit, fit only for white trash and lowlanders.

“The men are weather-beaten and have tiny wrinkles about their eyes. Their loose-kneed, shambling gait is ungraceful, but deceptively fast, whether they strike out for town six or eight miles away, or are just making a circle to kill a few squirrels.”

MULE POWER

Arkansas agriculture was becoming more mechanized as World War II loomed, progress reflected in this tribute to the mule:

“Though their number has declined since tractors took over much of the level land, mules are still preferred to horses in cotton fields. The mule is tough, stubborn and wiry. He drinks water so muddy that a self-respecting horse would snort at it. He humps his back to a wintry wind and nibbles forage a mustang would scorn.”

On Saturdays, farmers and their families would head to the nearest town. Main Streets were the centers of shopping, well before the advent of shopping malls on arteries leading to interstates and other highways. This is what it was like in Blytheville:

“Main Street is a wide sunny avenue lined with brick stores and offices. Shoppers are most numerous on Saturdays. On this day, the stores put on extra clerks, barbecue and hamburger stands prepare for a rush, and the motion-picture theaters bill Western thrillers.

“Farm people pack the sidewalks to sell produce, buy groceries and drygoods, and meet their friends. Sacks of feed and coops of squawking chickens are piled high outside the stores at the eastern end of Main Street. Perhaps a huge catfish, fresh-hooked from a Mississippi slough, dangles before a lunchroom.”

Hot Springs was also lively as it welcomed tourists, but with leisure activities mostly different from today:

“Outdoor photograph studios, where visitors have their pictures taken astride a slumbering burro or behind a prop saloon bar, spring up in vacant lots next to sumptuous hotels. Small shops serve fresh seafood, fruit juices or goat’s milk. Stands display crystals, curios, souvenirs and trinkets. In the narrow canyons, patrons of shooting galleries blaze away into the mountainside.”

The guide’s 1987 reprint added a new introduction by Elliott West, a University of Arkansas, Fayetteville historian. He asserted that “if there is a common theme uniting the past and the present and the state’s various parts, it is that of poverty.”

That is less true in 2021 in the state’s metropolitan areas, but it remains a lamentable fact of life in many small towns and rural areas. Per-capita income in Arkansas today ranks 45th among the 50 states.

RHAPSODIES

But the opening pages of the original edition cite Arkansas’ non-monetary treasures. These other avenues of pleasure are described in rhapsodic terms, which curmudgeonly readers might view as saccharine:

“Part of the wealth of Arkansas today is not in its minerals and forests, but in the sights and sounds encountered by a visitor.

“It may be the small thunder of a covey of quail that he will remember longest, or a flight of mallards wheeling down into a swamp because of a hunter’s expertly rendered call, or the bright glow of straw stacks burning in the rice fields after threshing time. The zigzag rail fences overgrown with honeysuckle, the clear smokeless air in the cities, the tumbling of the mountains eastward from Winslow, the smell of wood smoke from a great stone chimney at the end of a cabin, the pungency of pine sawdust and the whine of the saw biting into a log, the clumps of mistletoe in leafless trees.

“You won’t forget these things soon, even though they are not the important aspects of Arkansas, where the politeness of the South and the friendliness of the West are both responsible for the personal tone in ‘Y’awl hurry back.'”

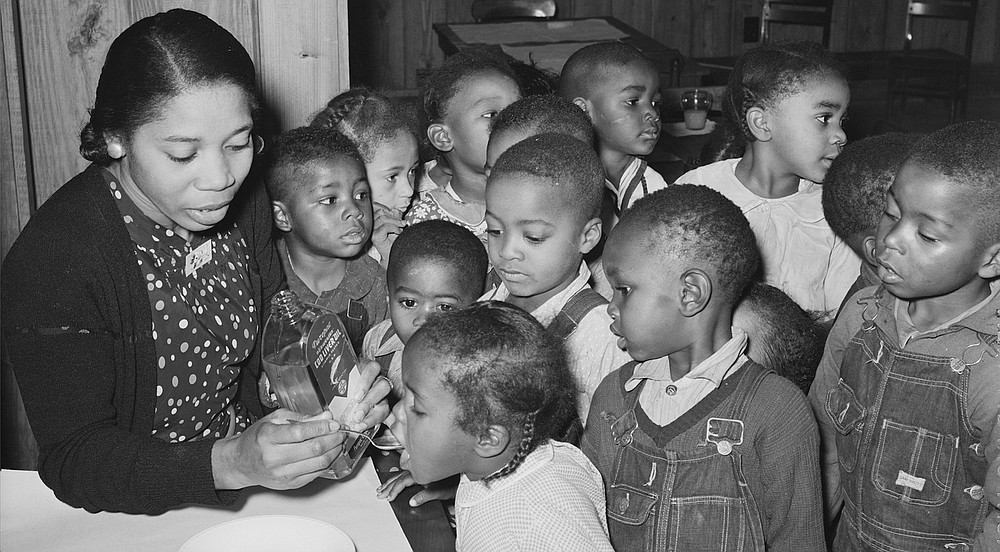

It was time for cod liver oil in the nursery school when Farm Security Administration photographer Russell Werner Lee (1903-1986) visited the Lakeview Resettlement Project, 15 miles southwest of Helena, in December 1938.

(Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division)